-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Antonio Rispo, Massimo Imbriaco, Luigi Celentano, Antonio Cozzolino, Luigi Camera, Pier P Mainenti, Francesco Manguso, Francesco Sabbatini, Patrizia D'Amico, Fabiana Castiglione, Noninvasive Diagnosis of Small Bowel Crohn's Disease: Combined Use of Bowel Sonography and Tc-99M-Hmpao Leukocyte Scintigraphy, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 11, Issue 4, 1 April 2005, Pages 376–382, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MIB.0000164020.65106.84

Close - Share Icon Share

Crohn's disease (CD) is frequently localized in the small bowel, with the diagnosis of disease and the assessment of its extension made by ileo-colonoscopy (IC) and small bowel enteroclysis (SBE). Transabdominal bowel sonography (BS) and Tc-99m-HMPAO leukocyte scintigraphy (LS) are increasingly used for the diagnosis of CD because of their minimal invasiveness, reproducibility, and acceptable costs.

From March 2000 to July 2003, we performed IC, SBE, BS, and LS in 84 patients with either suspected or known small bowel CD.

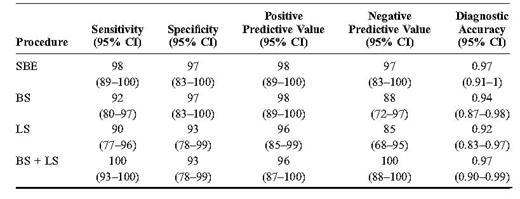

Small bowel CD was present in 50 patients, whereas the other 34 patients received a different diagnosis. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and diagnostic accuracy were, respectively, 98%, 97%, 98%, 97%, and 0.97 for SBE; 92%, 97%, 98%, 88%, and 0.94 for BS; and 90%, 93%, 96%, 85%, and 0.92 for LS. In addition, the combined use of BS and LS led to overall sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and diagnostic accuracy of 100%, 93%, 96%, 100%, and 0.97, respectively. BS showed a fair concordance with SBE in terms of location (k = 0.71) and a correlation with the extension of the disease (r = 0.67, P < 0.001). LS showed a concordance with SBE with regard to location in about one-half the population (k = 0.54), whereas it was less effective than SBE in defining disease extension.

BS and LS are 2 accurate techniques for the diagnosis of small bowel CD, and their combined use can be recommended as an early diagnostic approach to patients in which the disease is suspected. SBE remains the best procedure for the definition of the location and extension of the disease.

Crohn's disease (CD) is frequently localized in the small bowel, with or without colonic involvement.1,2 Currently, the diagnosis of small bowel CD and the assessment of its extension are performed by ileo-colonoscopy (IC) and small bowel enteroclysis (SBE), in view of their high sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy.3,–5 Unfortunately, IC is an invasive and expensive procedure and often requires an expert operator.6 In effect, ileal intubation is successfully performed only in 75% to 90% of endoscopies7,8; also, a further limiting factor is represented by the need for adequate bowel cleaning, which is obtained in, at most, 85% of patients undergoing IC.9 Similarly, SBE is expensive and invasive, causes x-ray exposure, and requires conversion to follow-through examination in about 19% of cases because of intolerance or refusal of naso-jejunal or oro-jejunal intubation.10 Alternatively, the follow-through x-ray procedure has shown the same diagnostic accuracy of SBE for CD diagnosis,11 but these data have been strongly criticized for procedural bias.12 More recently, wireless capsule endoscopy,13 computed tomography techniques,14 and magnetic resonance imaging15 have been proposed as useful methods for the diagnosis of small bowel CD, but all techniques are still expensive, and the proper role in clinical practice is not yet well established.

Transabdominal bowel sonography (BS) and Tc-99m-HMPAO leukocyte scintigraphy (LS) are two procedures that are increasingly used for the diagnosis of CD because of their minimal invasiveness, reproducibility, and acceptable costs. BS can visualize and locate transmural bowel inflammation, showing the alteration of the echo-architecture of the bowel wall in CD.16 It has been reported that the technique is accurate in identifying CD in the differential diagnosis of ulcerative colitis17 and in assessing the extent of the disease, with the exception of the stomach and of the deep pelvic tract of the sigmoid colon.18 Many authors have found that BS is an accurate method for the detection of intestinal complications in CD and that it compares favorably with SBE in the detection of obstruction, being able to correctly identify 90% of strictures documented by small bowel enema and confirmed at surgery.19 Furthermore, BS has proven effective for the diagnosis of postsurgical recurrence.20 LS has been used for many years in the investigation of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease because of its minimal invasiveness.21,22 The procedure is based on the ability of Tc-99m-HMPAO-labeled leukocytes to accumulate into the inflamed tissues (i.e., gut and joints). LS has previously shown a sensitivity of 76%, a specificity of 91%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 82% for ileo-colonic CD23; the diagnostic accuracy of LS seems to increase in presence of CD involving the terminal ileum.24 In addition, LS has shown a good correspondence with the spiral computed tomography findings23 and a high sensitivity for the diagnosis of postsurgical recurrence of CD.25 More recently, LS has been effectively used in the investigation of seronegative spondyloarthropathies,26 which often complicate CD.27

However, comparative data about the diagnostic accuracy of all these procedures in patients with CD are scanty. The aim of this study was the evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of SBE, BS, and LS in the diagnosis of small bowel CD.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively studied 106 consecutive subjects who attended our Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Clinic between March 2000 and June 2003 for either known or suspected small bowel CD. We proposed that all these patients undergo IC, SBE, BS, and LS; all patients gave their written informed consent to the study.

Six patients (6%) were excluded because of intolerance of intubation for SBE. In 16 patients (15%), ileal intubation during the endoscopy was not performed because of technical difficulty, inadequate bowel cleaning, or limited colonoscopy. Thus, 84 patients were considered in the study. Twenty of these 84 patients had received a previous diagnosis of CD and were being followed up at our IBD Unit; 10 of them had undergone previous surgery with ileo-colic anastomosis. The remaining 64 patients were studied for suspected small bowel CD. All 84 patients underwent IC with biopsy, SBE, BS, and LS within 10 days. The procedures were performed with the operators blinded about the result of the previous examinations. The investigators were not privy to the results of the biochemistry and were aware of any surgical resection previously performed.

The diagnosis of small bowel CD was made according to the ileoscopical and histologic findings28,29; the diagnosis was also confirmed at surgery when indicated.

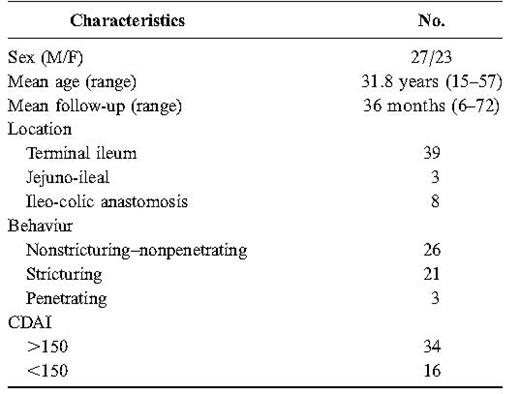

The patients with a diagnosis of CD were stratified according to the Vienna Classification30 and had their biochemical and clinical disease activity parameters recorded [erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C reactive protein (CRP); CD activity index CDAI)].

All patients were followed up for at least 12 months.

IC

IC was performed by an expert operator with a conventional colonoscope (Fujnon EC-410MP, Willieh, Germany; 150 cm) after a liquid dietary regimen of 48 hours and an oral bowel cleaning with 90 mL of oral sodium phosphate the day before the examination. The intubation of the ileo-cecal valve was performed according to a previous report.6 All patients underwent ileal biopsies. Endoscopic and histologic diagnosis of CD was made according to the literature.2,28,29

SBE

SBE was performed by oral intubation without sedation after an overnight fast. A preselected amount of barium and methylcellulose was infused through a catheter positioned at the duodenojejunal flexure as described by Herlinger.31 Compression views were obtained in all patients for the evaluation of the terminal ileum. Three categories of lesion were defined according to Engelhom et al.32 In brief, fold thickening, aphthous ulcerations, and granular appearance of the villi were considered to be early lesions. The nodular pattern and the presence of ulcerations on the mesenteric border characterized intermediate lesions, whereas “cobblestoning” appearance, fixed mechanical obstructions, and fistulae were considered to be advanced lesions. In case of diagnosis of CD, the radiologist would also describe the exact location and extension of the disease.

Transabdominal BS

BS was performed in the morning hours after an overnight fast using an Aloka SSD-1700 with linear and convex probes (5-7.5 MHz). No special preparation was prescribed. The procedure was performed by a gastroenterologist with experience in BS. In every patient, the entire abdomen was systematically scanned starting from the right iliac fossa. The bowel wall thickness was measured both in longitudinal and transverse sections and was considered normal for values up to 3 mm.33 In accordance with Maconi et al,19 stricture was considered present at BS examination when there was coexistence of thickened (>4 mm) and stiff intestinal wall, narrowed intestinal lumen, and fluid-distended or echogenic content-filled loops just above the thickened intestinal tract. Entero-cutaneous, entero-enteric, and entero-mesenteric fistulas were considered present when hypoechoic duct-like structures with fluid or air content were seen between skin and intestinal loops, between two intestinal loops, or between intestinal loop and mesentery, respectively.34 The presence of abscesses was evaluated according to the current literature.35 In case of diagnosis of CD, the gastroenterologist would describe the exact location and extension of the disease.

LS

Fresh venous blood (20-50 mL) was drawn from each patient into a 50-mL plastic sterile syringe containing 5 to 10 mL of acid-citrate-dextrose. Five milliliters of hydroxyethyl starch was added and mixed gently. Sedimentation at room temperature was then allowed. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged for 5 minutes (900g). The cell pellet was collected, resuspended in 5 mL of plasma, and carefully layered onto the upper part of the double Hystopaque gradient (Fycoll/Hypaque; density = 1.14), which was centrifuged at 700g for 20 minutes. The layer of granulocytes was collected with a sterile disposable 2-mL pipette and resuspended in 5 mL of the cell-poor plasma. The autologous leukocytes were prepared according to a previously published method.36 The labeling efficiency (mean and SD) was 77.4 ± 13.5%; white blood cell count median (range) = 6.9 (4 − 10.1) × 109/L. The final mean dose administered was 185 ± 74 MBq, depending on the labeling efficiency. Scintigraphy was performed using a GE Starport 400 AT gamma camera (General Electric) equipped with a low-energy medium-resolution collimator. Anterior and posterior images of the abdomen were obtained at the time of injection by means of dynamic framing acquisition (1 frame/min/30 min). After static acquisitions were done, we performed a spot view of abdomen at 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes (and) a whole body study in anterior and posterior projections. The scintigraphy was considered positive for IBD only when uptake of labeled autologous granulocytes was seen-along development of the bowel-within 1 hour from the injection of labeled cells. The activity scoring method, previously described,37 was applied to grading uptake. In cases of faint uptake or ambiguous results, the imaging was repeated later, in the same mode as described. However, the activity detected in the gut beyond 3 hours, from the cells reinjection, was considered doubtful, meaning IBD. To analyze the scintigraphy, all bowel was divided into 9 segments (jejunum, ileum, terminal ileum, cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum).

Statistical Analysis

To test the consistency between SBE, BS, and LS for CD location, Cohen's k measure was applied. Bivariate correlation about CD extension between SBE and BS was calculated by computing Spearman's coefficient with the significance level. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package for Windows (release 12.0.1.; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the single procedure were calculated using StatsDirect statistical software (release 2.3.8). With the same software, we also calculated the aforesaid statistics for the parallel combined use of BS and LS (BS + LS), defined as a positive result on at least one of the two procedures. Accuracy of SBE, BS, LS, and BS + LS as predictors of CD was determined with the concordance (c)-statistic, which is identical to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for binary outcomes.38,39 This statistic may vary from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating perfect discrimination and 0.5 indicating what is expected by chance alone.

Results

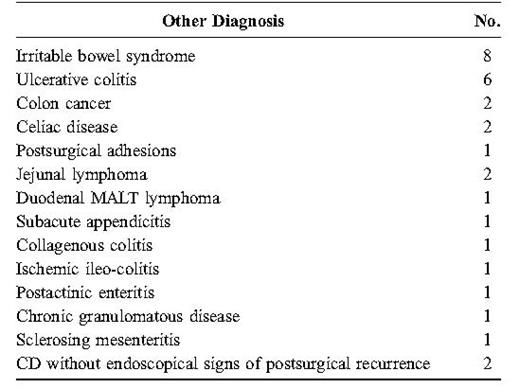

CD diagnosis was made in 54 of 84 patients. Fifty patients presented a small bowel CD with the involvement of the terminal ileum (Table 1). The remaining 4 patients had an isolated colonic CD and were excluded from the study. The last 30 subjects received a different diagnosis (Table 2). For 7 of these 30 patients, the final diagnosis was confirmed at surgery (2 colon cancer; 2 jejunal lymphoma; 1 sclerosing mesenteritis; 1 subacute appendicitis; and 1 postsurgical adhesion). In the other 23 patients, the diagnosis was validated by clinical follow-up; in some cases, with further investigations (7 computed tomography scans; 3 upper gastrointestinal endoscopies; 3 laparoscopies; and 3 laboratory studies).

The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and diagnostic accuracy of SBE, BS, and LS are reported in Table 3. All procedures showed high diagnostic accuracy (i.e., Figs. 1–3). Furthermore, the parallel combined use of BS and LS led to overall sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and diagnostic accuracy of 100%, 93%, 96%, 100%, and 97%, respectively.

SBE. Crohn's ileitis: the inflammatory involvement of the terminal ileum with a stricturing complication of disease is evident.

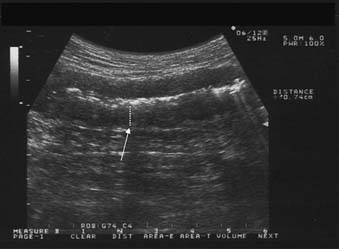

BS. Crohn's ileitis: the thickened wall (arrow) of the ileum with narrowed lumen is evident.

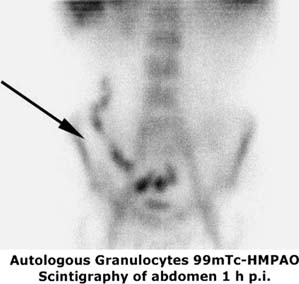

LS. Crohn's ileitis: the uptake of the labeled leukocytes into the terminal ileum is evident.

With regard to sensitivity, SBE showed signs of disease in 49 of 50 patients. The only CD patient with negative SBE had mild apthoid inflammation at ileoscopy. Forty-six of 50 patients with CD were positive at BS. The 4 patients with negative BS had mild inflammatory ileitis; 2 of them also presented involvement of the deep pelvic ileum. LS showed a significant uptake of leukocytes in 45 of 50 patients with CD. Three of the 5 false-negative patients had extensive jejuno-ileal CD, whereas in 1 patient, the labeling of leukocytes had been unsatisfactory. For the last false-negative case, the uptake was ascribed to the sigmoid colon while inflammation was present in the terminal ileum.

Thirteen of the 50 patients with CD (26%) underwent surgery within 6 months; in all these cases, the diagnosis was confirmed at surgery. Both BS and LS showed a high sensitivity for the diagnosis of postsurgical recurrence (87%), with a sensitivity of 100% for their combined use.

In terms of specificity, SBE gave one false-positive finding among the 30 patients without CD; this case was diagnosed as jejunal lymphoma by spiral computed tomography, and the diagnosis was confirmed at surgery. With BS, 1 false-positive result was found in a case of sclerosing mesenteritis. LS showed 2 false-positive outcomes: 1 in a case of bleeding jejunal lymphoma and the other in a case of ulcerative colitis.

SBE and BS could be compared with regard to the assessment of the location and extension of CD in 45 patients. In these patients, BS showed a fair concordance with SBE both in terms of location (k = 0.71) and extension of the disease (r = 0.67; P < 0.001; Fig. 4). As for the intestinal complications of CD, BS detected 12 of the 14 strictures identified by SBE (85%), 4 of the 5 fistulas highlighted at radiology (80%), and 3 abdominal abscesses not shown at SBE (7%).

Scatterplot showing the correlation between the CD extension, expressed as centimeters, assessed by SBE and BS.

LS and SBE were comparable in 44 patients. In about one-half of these cases (k = 0.54), LS showed concordance with SBE with regard to the location of disease, although it could not indicate its extension because the procedure does not allow an exact measurement of the pathologic intestinal tract. In addition, LS detected the presence of subclinic arthropathy in 4 of the 50 patients with CD (8%).

Also, compared with the indexes of activity of disease, positive LS presented a poor correlation with the biochemical inflammatory parameters (LS-ESR: k = 0.12; LS-CRP: k = 0.19) and CDAI (LS-CDAI: k = 0.17).

Discussion

CD is frequently located in the small bowel, particularly in the ileum.1,2 IC allows the visualization of the inflamed bowel tract and the collection of biopsies for the histologic evaluation of the suspected disease; therefore, it is considered the most accurate procedure in the diagnosis of ileal CD. Unfortunately, ileal retrograde intubation is not always performed,6,8,9 and CD can, at times, spare the terminal ileum, so that the disease can be left undiagnosed. Therefore, despite being invasive and expensive, SBE is currently considered the most accurate procedure in the diagnosis of small bowel CD and in the assessment of its extension.4,5

The invasiveness of the radiological and endoscopic procedures is a very relevant issue. In fact, such invasiveness can make the clinician reluctant to recommend these investigations at an early stage of the diagnostic approach to a case of suspected CD, especially in the presence of mild symptoms or only slight biochemical alterations, thus causing a delay in the diagnosis.40

Transabdominal BS and LS are 2 techniques that are increasingly used for the diagnosis of CD because of their minimal invasiveness, reproducibility, and acceptable costs18,21 and could be very useful in the diagnostic approach to a suspected CD.

In our study, CD diagnosis was made in 54 of 84 patients (64%); this high percentage of CD is probably caused by a referential bias of the patients to a third level IBD center.

Our experience has confirmed the high diagnostic accuracy of SBE for the diagnosis of small bowel CD4,5 compared with IC, showing a better definition of both CD location and extension once matched up against BS and LS. Our data also indirectly confirmed that the sensitivity of SBE is slightly higher then that reported for small bowel follow-through in previous reports.41

Similarly, BS and LS showed high diagnostic accuracy for CD (94% and 92%, respectively), with a reduction in information in case of extensive jejuno-ileal disease for LS and of involvement of the pelvic ileum for BS. In comparison with enteroclysis, BS revealed a good correlation with regard to intestinal complications such as strictures and fistulas, additionally showing the presence of abscesses.

Furthermore, a positive LS showed poor correlation compared with ESR, CRP, and CDAI; as already known, histologic and endoscopic findings of bowel inflammation activity, of which LS is an indirect expression, do not closely correlate with the clinical and biochemical parameters of the disease,42 thus justifying this result.

Regarding specificity, both SBE and LS gave 1 false-positive finding in a case of jejunal lymphoma; therefore, this differential diagnosis seems to be the most relevant issue in a case of suspected isolated jejunal CD.

Interestingly, in our experience, the parallel combined use (with positivity of at least 1 of the 2 performed procedures) of BS and LS led to an overall sensitivity of 100% with the same diagnostic accuracy of SBE (97%), with the disease being diagnosed in all cases. The combined approach also showed a sensitivity of 100% for the diagnosis of postsurgical recurrence. In addition, this combined diagnostic approach offered the benefit of detecting intestinal and extraintestinal complications of CD in many patients, allowing in these cases, an early “whole body” staging of the disease. Therefore, this noninvasive combined approach could be very useful to select the patients to expose to subsequent SBE examination for the confirmation of CD diagnosis and the accurate assessment of the location and extension of the disease. Also, the combined use of BS and LS showed a negative predictive value of 100%; as a result, the patients with negative BS and LS would not require further investigations to exclude the diagnosis of small bowel CD.

In conclusion, BS and LS are 2 accurate techniques for the diagnosis of small bowel CD, and their combined use can be recommended as an early diagnostic approach to patients with suspected disease. SBE remains the best procedure for the definition of the location and extension of the disease.

References

Author notes

Reprints: Antonio Rispo, MD, Gastroenterologia Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia, Università “Federico II,” Via S. Pansini 5, 80131 Naples, Italy (e-mail: antoniorispo@email.it)